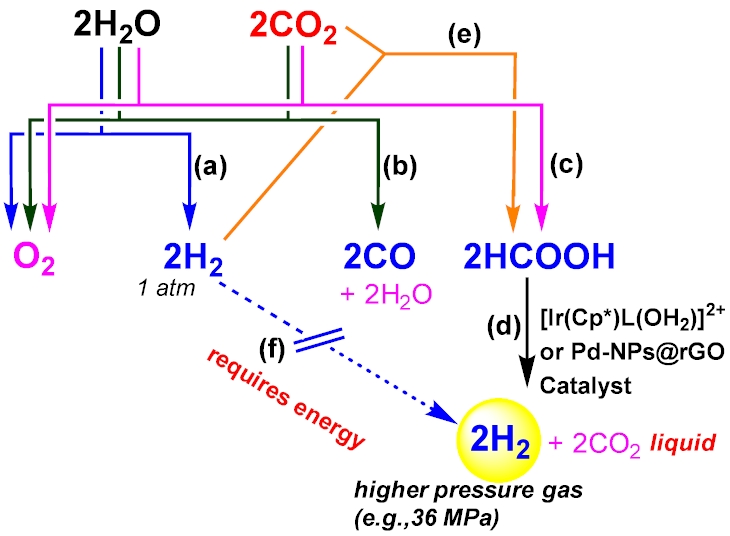

The production targets in artificial photosynthesis focus on hydrogen (H2), formic acid (HCOOH), methanol (CH3OH), ethanol (C2H5OH), methane (CH4), etc. To create all these energy carriers, renewable energy sources such as solar and wind are required to drive reduction of proton (H+) or carbon dioxide (CO2). While hydrogen is the simplest and cleanest energy carrier, ensuring the zero CO2 emission upon utilization, the gaseous nature of hydrogen poses significant challenges in handling, particularly in storage and transportation, compared to liquid energy carriers, such as formic acid, methanol, and ethanol. The primary research focus is thereby on the utilization of formic acid, considering its several advantageous properties as a high-density hydrogen carrier. Formic acid is even obtainable by combining hydrogen with CO2 (scheme e), resulting in a combustion energy nearly equivalent to that of hydrogen. Because of their roughly equivalent energy capacity, hydrogen and formic acid are highly compatible as energy sources. Moreover, formic acid can be converted back into hydrogen by using a catalyst to speed up the process—such as the iridium or palladium catalyst shown in the figure (reaction d).

For all photosynthetic schemes (a-c), we must catalytically promote “water oxidation”, liberating oxygen (O2) from water. This step is essential to extract the electrons and protons required to produce energy carriers, as carried out in natural green plants. Regarding this fundamental catalysis, my research group has established a significant foundation of knowledge and expertise through various high-impact studies (e.g.,

Chem. Comm. 2012,

Chem. Comm. 2013;

ChemSusChem 2014,

Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2019;

ACS Catal. 2023;

JACS 2024). I intend to leverage this extensive experience to successfully advance my resaerch in the coming years.

On the other hand, there is a significant drawback to following schemes (a) and (b), as they yield potentially explosive gaseous mixtures (i.e., 2H2/O2 or 2CO/O2). They inevitably require the extra costs and energy for gas separation. In contrast, formic acid production coupled with water oxidation by following (c) is a promising renewable energy cycle. Since formic acid remains in the aqueous phase while oxygen is released as a gas, the products separate spontaneously, eliminating the need for complex separation processes. This feature is particularly relevant to the production of high pressure hydrogen fuel (scheme d), where formic acid is

catalytically converted into high-pressure hydrogen (>36 MPa) and liquid CO2. This approach offers a compelling way to bypass energy-intensive mechanical compressors (scheme f), significantly reducing energy consumption and infrastructure costs. Such an innovation creates a vital opportunity for developing H2-refueling stations for the hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, like Toyota Mirai. Further, the technology enabling the reversible hydrogenation of CO2 into formic acid (scheme e), must be advanced to facilitate the large-scale transportation of hydrogen energy in liquid form. Additionally, Direct Formic Acid Fuel Cells (DFAFCs), which convert liquid formic acid into electricity, have the potential to meet sustainability goals, especially if formic acid is produced from the CO2 captured from the atmosphere. To advance these critical technologies, we recently explored the factors governing formate (HCOO-) selectivity in CO2 reduction (

ACS Catalysis 2024;

JACS 2024). Our findings demonstrated that the hydride intermediates – essential for selective formate formation - must be precisely designed to suppress the competing and undesirable proton reduction into hydrogen.